You are currently viewing the whole syllabus; go back to default view.

The speed of loading and viewing the syllabus may be slower when showing a large amount of content.

Course Requirements

- Attendance: you are required to attend at least ten seminars.

- Writing: Preparation of written solution of assigned scenario (approx. 10 000 characters). Scenarios will be assigned on 16th March.

- Presentation: defence and discussion of the written solution on 18th May.

23.2. Cybersecurity and Cyber-defence law - system and principles (POLČÁK)

One might

sometimes get an impression that cyberlaw is a novel discipline. In fact, it is

not. It has been around for more than three decades and many of its areas are

already well established, including doctrine, case-law etc. Cybersecurity law,

however, is a bit different story. It instantly emerged mostly thanks to

specific legislation that started appearing around the world not even ten years

ago. Cyber-defence law is even younger with black-letter laws only developing and

nearly no case-law - despite we now have plenty of case studies of actual cyber-defence

incidents.

In this

first module, we will look at the overall picture of cybersecurity and

cyber-defence as a regulatory agenda. In particular, we will identify main

regulatory issues and challenges and see how they are systematically tackled in

international, European and national laws. We will also talk about fundamental

institutional distinctions between security, law enforcement and defence. These

fundamental elements will serve us also as a basis to understand cultural

differences that make it often difficult to establish functioning international

cooperation in cybersecurity as well as to identify similarities that, to the

contrary, serve as an enabler of closer cooperation between certain nations.

In

addition, we will briefly tackle basic regulatory concepts that are used in

cybersecurity laws, namely performance-based rules, smart rules and public-private-partnerships

and discuss quite unique dynamics of compliance and liability. For

cyber-defence law, we will briefly discuss the so-called ‘paradox of big guns’

that makes law making, incl. drafting of international treaties, mostly

challenging.

We chose as

a basic text for this module the following chapter from the upcoming Edward

Elgar book ‘Data Governance in AI, FinTech and LegalTech’ edited by Joseph Lee. The

chapter, as well as the whole book, is primarily about IT in financial services.

However, the core of the chapter explains in general the above regulatory concepts that do

not only work in fintech, but are of universal nature. When reading the text, you can skip the parts that specifically refer to fintech and financial services.

Please, note

that the following text is an unpublished manuscript that is copyrighted by

Edward Elgar. It can be used only for educational purposes in this course and

it is strictly prohibited to make copies, distribute it or even cite it.

2.3. International cybersecurity law (HARAŠTA)

9.3. Incidents and cyber-operations - case studies (BÁTRLA)

Resources for the lecture

The aim of this lecture is for you, students, to have a better understanding of various aspects of cyber incidents and operations. Various perspectives illustrated on a real-world case studies will include a selection from policy, strategic-operational-tactical, even to a bit of technical and business facets of cybersecurity.

While one lecture is never sufficient to cover these, I hope to give you some pointers for whichever field you would like to delve more into.

Please, use resources below to help you prepare for the lecture, including questions and discussion points you would like for us to cover. Also do not hesitate to ask about anything you could not understand from resources below, because it is completely normal to do so, given how broad cybersecurity is. :-)

Darknet Diaries (Podcast)

When it comes to describing cyber incidents, there is somebody who "won the Internet" (for the time being at least). That someone would be Jack Rhysider from Darknet Diaries podcast. So for a very interesting yet informative coverage of notable recent incidents and their impact, please check some episodes I selected below. They are mostly focused on state or state-supported threat actors, however help illustrate the real-world techniques, outcomes and damages we are talking about here. As well as how much expertise and preparation (especially when it comes to physical impact of cyber operations) is oftentimes required, compared to the Hollywood-style impression of cyberattacks we often come across.

NOTPETYA

Brief overview of the case: https://cyberlaw.ccdcoe.org/wiki/NotPetya_(2017)

Darknet Diaries EP 54: https://darknetdiaries.com/episode/54/ , transcript https://darknetdiaries.com/transcript/54

(Optional, for broader context. EP 53: SHADOW BROKERS: https://darknetdiaries.com/episode/53/)

TRITON

Brief overview: https://cyberlaw.ccdcoe.org/wiki/Triton_(2017)

Darknet Diaries EP 68: https://darknetdiaries.com/episode/68/, transcript https://darknetdiaries.com/transcript/68/

(Optional) Other interesting episodes include:

EP 48: OPERATION SOCIALIST https://darknetdiaries.com/episode/48/, also covered in the text below.

EP 50: OPERATION GLOWING SYMPHONY https://darknetdiaries.com/episode/50/ for behind the scenes on running a state cyber operation

Ross Anderson - Security Engineering 3rd. ed - "Who is the Opponent?"

Cybersecurity is multi-disciplinary field and often requires bridging the gaps into other areas. This text is indeed for security engineers, who are designing and building secure systems, thus a bit more technical in some parts. However, for us it serves as a great introduction to how broad cybersecurity actually is, shows most important actors and types of attacks we need to consider. This builds greatly on the more storytelling approach of Darknet Diaries and helps round the insights from individual cases into a broader concept.

Please, note that the following text is an online version for review that is copyrighted by Ross Anderson and Wiley publishing. Please, use it only for educational purposes in this course. For other available chapters, additional resources and full previous editions of the book (still worth reading!), visit: https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~rja14/book.html

16.3 Assignment of scenarios (HARAŠTA)

For background information (alternate reality), see slides 8 to 13.

For task no. 1, see slide 15.

For task no. 2, see slide 16.

For task no. 3, see slide 17.

For task no. 4, see slide 18.

For task no. 5, see slide 19.

For timeline, see slide 21 (for details slides 22 to 24).

For recommended resources, see slide 26.

If you have any question, reach out to me at jakub.harasta@law.muni.cz.

|

Student |

Uni ID |

Task: |

|

Achberger,

Viliam |

480173 |

1 |

|

Barešová,

Veronika |

480087 |

3 |

|

Borbély,

Kincső Krisztina |

530133 |

3 |

|

Bouček,

Patrik |

496915 |

4 |

|

Červinková,

Klára |

493909 |

2 |

|

Drappanová,

Denisa |

493922 |

4 |

|

Fráňa, Patrik |

480439 |

3 |

|

Franek,

Ondřej |

480132 |

4 |

|

Fryda,

Dominik |

492740 |

5 |

|

Galia, Martin |

494158 |

5 |

|

Grasso, Maria

Chiara |

530197 |

4 |

|

Hönigová,

Sandra |

455539 |

3 |

|

Jirásek,

Matyáš |

494198 |

5 |

|

Juřička,

Vojtěch |

480557 |

1 |

|

Korčák,

Matouš |

493845 |

4 |

|

Koutný,

Ladislav |

492714 |

5 |

|

Kováčiková,

Michaela |

493782 |

2 |

|

Petrová,

Sofie |

480298 |

2 |

|

Příborská,

Monika |

493717 |

1 |

|

Vats, Aksha |

530892 |

2 |

|

Veselý,

Vojtěch |

480520 |

2 |

|

Werner, Jan |

493787 |

1 |

|

Zipser,

Martin |

484313 |

3 |

23.3. European Cybersecurity Law I - NIS Directive (POLČÁK)

In this module, we focus on the core cybersecurity legislation in the EU - the NIS Directive (or the directive concerning measures for a high common level of security of network and information systems across the Union):

The primary aim of the Directive was to unify the regulatory architecture of cybersecurity measures across the common market and provide for a collaborative framework on the level of the EU. The following document summarizes the aims and content of the Directive:

In class, we will focus namely on the following aspects of the NIS Directive:

- constituency (subjects and systems covered)

- compliance (protective and preventive measures)

- incident reporting and functioning of CSIRTs

- institutions and powers (incl. cooperation on the EU-level)

Regulatory and cooperative measures introduced by the NIS Directive represent only a part of cybersecurity laws that were developed by the member-states - partly because some areas that are covered by national cybersecurity laws fall outside the EU domain. Also, the NIS Directive left quite a broad space for the member-states to decide whether and how various measures will be legislated and implemented. Consequently, there are big differences in national cybersecurity laws among the member-states as shown on the following reference page (the following resource is only informative - particular cybersecurity laws of member-states fall outside of the scope of this course):

As the Commission, as well as the member-states, recently gained extensive experience with the application of the NIS Directive, there has been held extensive debate about improving the EU cybersecurity regulatory framework. In result, there is currently pending a legislative draft that aims replacing the NIS Directive (referred also to as NIS II) with anticipated coming into force around the beginning of 2024.

30.3. European Cybersecurity Law II - Cybersecurity Act (POLČÁK)

This part is primarily about cybersecurity certification in the EU. A certification mechanism was a missing element in the logic of the regulatory framework of EU cybersecurity since the adoption of the NIS Directive (or even earlier when member-states adopted their own cybersecurity laws - just as the Czech Republic).

Essential service operators and other regulated subjects had (and still have) to face considerable uncertainty when national laws laid down performance-based requirements for organizational and technical arrangements that were not particularly defined. Broad flexibility of respective rules provide essential service operators, on the one hand, for an opportunity to develop efficient and even creative solutions that are envisaged to be tailor-made for their specific needs. On the other hand, essential service operators that develop such solutions lack an a priori assurance that they are legally sound. In result, the regulatory model using performance-based rules that worked primarily with compliance approach (instead of liability) lacked an essentially important mechanism for officially-backed checking of the actual regulatory compliance.

In this class, we discuss the cybersecurity certification mechanism, as laid down by the Cybersecurity Act. First part of the Act is dedicated to the establishment of ENISA as the main EU agency for cybersecurity. Cybersecurity certification is legislated under Title III (from Art. 46).

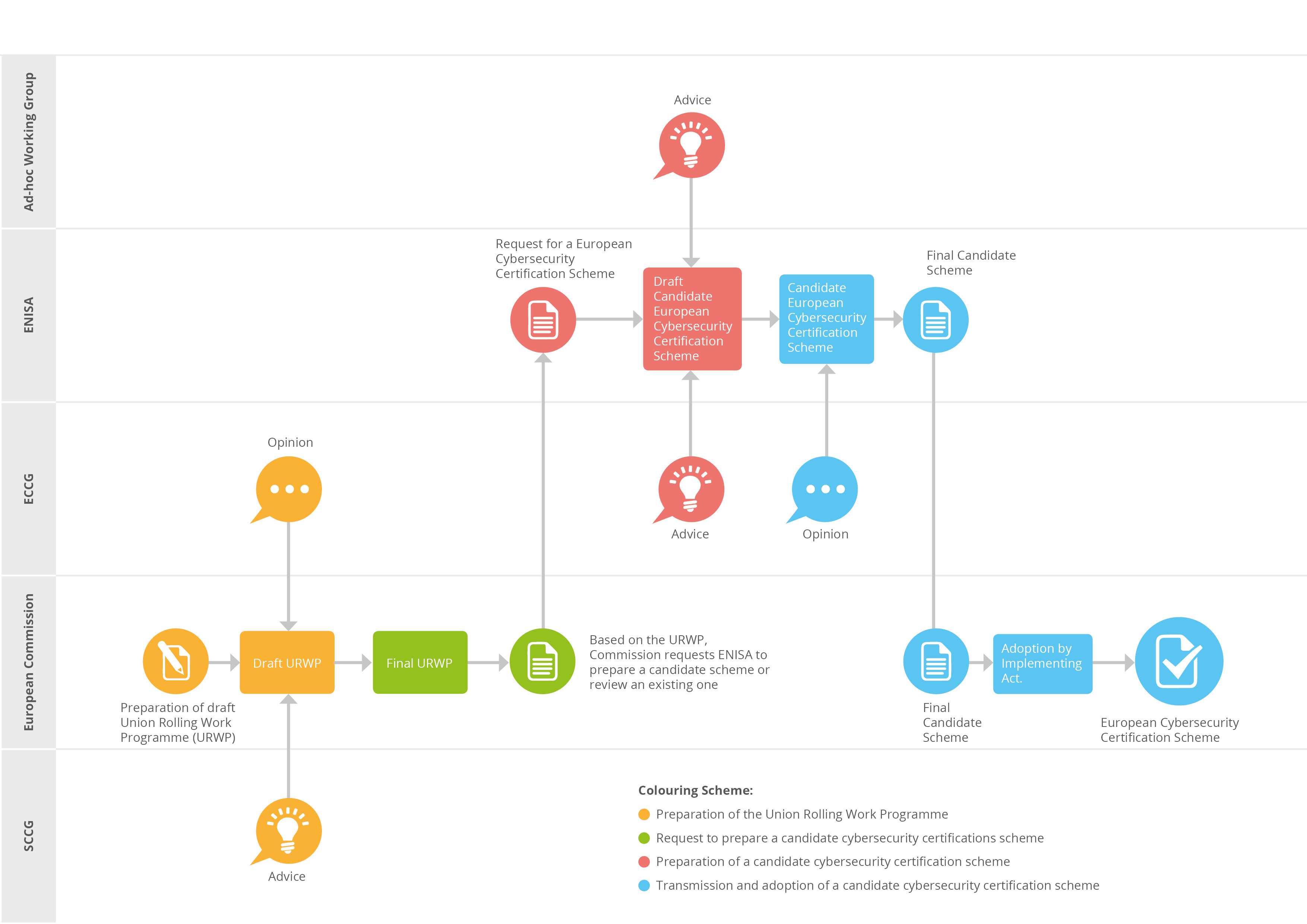

The mechanism is based on cybersecurity certification schemes. These are issued by the Commission in a procedure that is mostly mediated by the ENISA. We discuss the procedure and its actors in class and it can be demonstrated on the following diagram:

The mere certification can cover products and services, but also processes. In result, it is possible to imagine certification schemes that would be primarily aimed even at certification of vendors and their development or deployment processes. In class, we discuss why and where this approach might be relevant. Currently, there are pending two certification schemes (the following link is just for information regarding the current state of play - it is not necessary to view its content):

We also discuss in class the levels of assurance and subsequent differences in respective certification procedures as well as complex institutional backing of accreditation of conformity assessment bodies (CABs) and of mere certifications. A simplified overview of these processes is also available here as a video:

Here is the presentation that is used in class:

6.4. Institutional backing of cybersecurity in Europe (POLČÁK)

In this part, we tackle the institutional backing of cybersecurity. Any legal, technical or organizational measure is quite useless if it is not backed by relevant and capable institutions, public or private. In cybersecurity, we assume relatively poor capability of state regarding complex information systems and communication infrastructure. That is why the regulatory model of European cybersecurity uses performance-based rules. Consequently, the fundamental level of rule-making goes after the regulated subjects, in particular:

- Essential service operators

- Digital service providers

EU member-states often work with more sophisticated structure of regulated subjects that include also other private and public institutions outside the scope of NIS Directive-based definitions of essential and digital services. In addition, the scope of national laws often includes, besides owners or controllers (operators) of respective systems and networks, also units, mostly private, that provide services or equipment to the operators on the basis of contracts. In particular, the Czech Cybersecurity Act works with the following structure (§3 of the Cybersecurity Act)

"a) An electronic communication service provider and an entity operating an electronic communications network1), unless they are public authorities or legal or natural persons specified in letter b)

b) A public authority or legal or natural person administrating an important network, unless they are the operator or the administrator of a communication system according to letter d)

c) An operator and an administrator of a critical information infrastructure information system

d) An operator and an administrator of a critical information infrastructure communication system

e) An operator and an administrator of an important information system

f) An operator and an administrator of an information system of essential service, unless they are the operator or the administrator specified in letters c) or d)

g) An operator of an essential service, unless they are the operator or the administrator specified in letter f)

h) A digital service provider"

The regulatory institutional framework consists primarily of national cybersecurity authorities. These are differently positioned in different member states – somewhere, it is a specific authority, while elsewhere this regulatory agenda is backed by an existing security authority, a law enforcement body or other governmental institution.

Another important difference among the member states is in the mere fact whether these institutions act as regulators. The NIS Directive does not envisage cybersecurity authorities to have their own regulatory powers, but individual EU member-states might entrust them with competences to issue various sub-statutory regulatory instruments.

Quite specific is the institutional framework of CSIRTs. The EU-level of this framework is explained in recital 32-33 as follows:

“ Competent authorities or the computer security incident response teams (‘CSIRTs’) should receive notifications of incidents. The single points of contact should not receive directly any notifications of incidents unless they also act as a competent authority or a CSIRT. A competent authority or a CSIRT should however be able to task the single point of contact with forwarding incident notifications to the single points of contact of other affected Member States.

To ensure the effective provision of information to the Member States and to the Commission, a summary report should be submitted by the single point of contact to the Cooperation Group, and should be anonymised in order to preserve the confidentiality of the notifications and the identity of operators of essential services and digital service providers, as information on the identity of the notifying entities is not required for the exchange of best practice in the Cooperation Group. The summary report should include information on the number of notifications received, as well as an indication of the nature of the notified incidents, such as the types of security breaches, their seriousness or their duration.”

Roles and responsibilities of CSIRTs do not only cover incident reporting, but they might also have some forensic competences, an ability to develop and use active countermeasures etc. At the seminar, we will specifically focus on cooperation of CSIRTs with national and international institutions in security, defense, law enforcement and intelligence.

Last (but not least) institutional issue that will be discussed in class relates to certification processes. The Cybersecurity Act counts with the following institutions:

- National cybersecurity cettification authorities

- National accreditation bodies - (EC) 765/2008

- Conformity assessment bodies

- Commission

- European Cybersecurity Certification Group (ECCG)

- Stakeholder Cybersecurity Certification Group (SCCG)

In class, we will discuss roles and responsibilities of the above institutions and bodies as well as associated legal and organizational issues.

13.4. Liability for cybersecurity incidents (POLČÁK)

This topic is not a coherent one. Liability takes very different forms and covers various aspects of cybersecurity measures and incidents.

The cybersecurity law as such is primarily based on compliance rather than liability. Regulated subjects, i.e. essential service operators and others, are obliged to develop, deploy and document their own cybersecurity measures, detect and report cybersecurity incidents and comply with potential regulatory orders issued by relevant authorities. In that respect, liability is mostly of secondary concern and covers violations of the above duties. We discuss in class namely administrative liability arising from investigative and directive powers of cybersecurity authorities, i.e. fines and administrative orders.

A special sort of indirect, yet quite interesting and pragmatically important, liability can be found in the Czech law. It is attached to a regulatory instrument of an 'official warning' that does not have per se direct liability consequences, but may induce private law liability. When authorities issue and officially communicate a warning, there arise no immediate duties or administrative sanctions, but regulated subjects are provably informed about an actual risk. It is a matter of their choice whether they undertake any action to respond to a warning - however, if they fail to do so and harm is caused as a consequent of such inaction, they might be held liable for failing to fulfill the general private-law preventive duty.

In any case, cybersecurity law is not primarily about liability. Its aim is to provide for secure environment rather than tools for identification and sentencing of perpetrators. Thus, most of the liability agenda related to cybersecurity incidents falls outside the scope of cybersecurity law.

In class, we discuss mostly typical liability cases that are rather frequent and complex. We mostly avoid liability of attackers - these cases are relatively seldom (because of lack of evidence). If evidence is sufficient, these cases are relatively straightforward from the legal standpoint, because criminal law provides for relatively well-suited typical crimes.

First typical, and quite problematic, case is the one of a negligent user. These cases appear when users let attackers to access their device through malware. In result, devices are either used as a gateway for intrusion, ransomware or spyware, or they are used as zombies for DDoS attacks. The main question of law is then whether users acted in negligence, i.e. whether they knew (or could have known) about the risk, and could have acted in order to avoid it. In class, we specifically discuss labour relations and options that the employer has in order to make negligent employees liable.

Another typical issue is the liability of active professionals. Active countermeasures taken against various sorts of cyberattacks might generate liability risks because of their possibly intrusive or destructive effects. It is then questionable, whether and when one might argue with self-help in cases of infringement of rights, or which active countermeasures are to be considered beyond legal. The same discussion can be also applied on penetration testing, ethical hacking etc.

As a bonus, although this method is not available in the continental law, we discuss quite a creative case of relatively well-balanced liability assessment of users who avoided security update of an operating system and exposed their devices to a botnet malware.

20.4. Securing critical infrastructures (HARAŠTA)

Supplementary literature (read after seminar)

27.4. Securing autonomous systems (ŽOLNERČÍKOVÁ)

-

Council

Directive 2008/114/EC of 8 December 2008 on the identification and

designation of European critical infrastructures and the assessment of

the need to improve their protection

- Regulation

(EU) 2019/881 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April

2019 on ENISA (the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity) and on

information and communications technology cybersecurity certification

and repealing Regulation (EU) No 526/2013 (Cybersecurity Act)

- Proposal for a Regulation laying down harmonized rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) - Articles 13, 15, 42, 43

- European Commission, Commission Report on safety and liability implications of AI, the Internet of Things and Robotics https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/commission-report-safety-and-liability-implications-ai-internet-things-and-robotics-0_en

- Artificial Intelligence and cybersecurity, CEPS, April 2021

- Should Artificial Intelligence Be Regulated? Issues in Science and Technology (issues.org), Summer 2017

- The publication of the CAHAI “Towards regulation of AI systems”, December 2020

- European Commission, White paper on Artificial Intelligence. Online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/white-paper-artificial-intelligence-european-approach-excellence-and-trust_en

4.5. Securing clouds (KLODWIG)

- Understand and explain what it is "cloud computing" and what types are rocognized

- Understand and explain the system of Czech regulation of cloud computing

- Understand and explain how EUCS will work and how it will comply with Czech regulation

- Understand and explain how to work with cloud computing catalogue

- Understand and orient in cloud computing decrees

- Understand and orient in cybersecurity requirements for cloud computing

- Understand the relationship in between Czech and European regulation of cloud computing

- EUCS – Cloud Services Scheme — ENISA (europa.eu)

- Title VI. - Act No. 365/2000 Coll. on Public Authority Information Systems

- § 4 Act No. 181/2014 Coll. + older version in English

- 315/2021 Coll., Decree on Security Levels for the Use of Cloud Computing by Public Authorities (zakonyprolidi.cz) + English version

- 316/2021 Coll., Decree on Some Requirements for Incorporation into the Cloud Computing Catalog (zakonyprolidi.cz)

+ English version

- NÚKIB - other cybersecurity legislation in English

11.5. Simulations and trainings (KYPO field trip) (STUPKA)

This module will take place in the KYPO lab, which is located in the building of the Faculty of Informatics (Botanická 68a, Brno), on 11.5. at 14:00. Please come through the main entrance, the arrows will guide you into the lab.